Speed Secrets: What It Takes to Drive the Limit

Do you need to crash every now and then to find the limit?

The ability to consistently drive a car at the limit takes a lot of time to develop the skills to do so. The best drivers in the world, who can drive at the limit very consistently, have been doing this almost all their lives. Gradually chipping away at finding the limit is the smart approach.

Do you need a couple of decades to learn to do this? No. (I’ll provide some tips at the end of this article to shave time off of that process).

Do you need to crash to find the limit? No.

Do you need to go slightly beyond the limit and then dial it back from there? Yes. The key is being able to go slightly beyond the limit, not to where you spin or crash, but where you just “get messy.” And then, you dial it back a tiny bit, smoothing it out to the point where you’re consistently at the limit. Or, at least more consistent.

Of course, your car control abilities are a big part of this. If you go slightly beyond the limit, but don’t have the car control skills to bring it back, it’s going to “hurt” sometimes. If you have the ability to go beyond the limit, and bring it back ninety-nine percent of the time, then you’re going to be able to drive consistently at the limit. The more time you spend practicing your car control skills (on a skid pad, loose/dirt surface, wet race track, dry track, etc.), the better you’ll be at controlling your car at the limit.

I bet the single biggest difference between you and, let’s say, Max Verstappen, is that he’s better at making mistakes. What? Yes, first, his mistakes are smaller than yours because he recognizes them sooner; and then, he’s made so many of them that he’s quite good at correcting them.

One take-away from what I just said is that you need to make more mistakes! And yes, in a way, that’s true. You need to get better at correcting the mistakes that you make, and learning from them. As I’ve said before, think of them as “learning-takes,” rather than mistakes.

One way of thinking about the experience you gain over time is that you’re simply getting better at correcting your mistakes.

But, it’s not just your car control abilities that make the difference. No, it’s also your confidence in your abilities. If you have the car control skills to drive at the limit, but don’t trust yourself or believe you can do that... well, that’s just as bad as not having the car control skills. So, to consistently drive at the limit takes skills and the belief in your skills. Through mental training, you can build up your belief in your own abilities.

It’s one thing to find and drive at the limit, but is your limit the same as mine, or Max Verstappen’s? In theory, the limit is the limit. Period. But some drivers create a limit that is slightly less than the theoretical limit. They’ve created an artificially low limit. Yes, they’re actually at the limit, but it’s not THE limit. Let’s dig into that.

What is the limit?

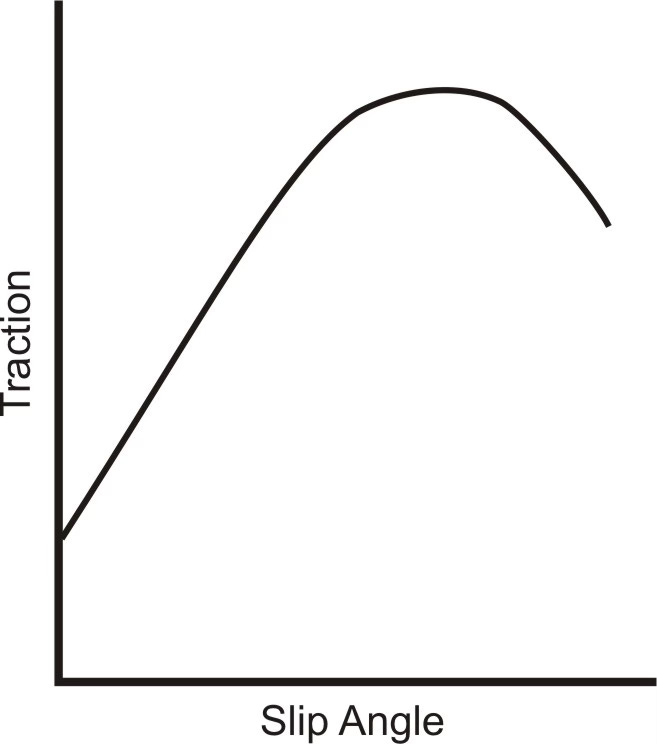

Take a look at a tire slip angle versus traction graph. You’ll notice that as a tire slips more, it increases its traction capabilities until it reaches a plateau, and then it tapers off. I’m sure you know that from a gut level perspective and feel — the faster you go, the more grip the tires generate, and then at some point if you continue to go faster, the tires start to lose grip and they slide too much. If you slide too much, you’ll spin or slide right off the track. And that’s the “big fear” of many drivers — to go way over the limit, and crash. But the slip angle versus traction graph also shows that the grip does not go immediately from “stuck” to “unstuck” without any warning. Some tires give you more warning, and some give you less — but they all give you some warning.

Hereʻs one way of looking at driving the limit: it’s when a pair of tires on your car are at the peak of the slip angle versus traction graph. Why not all four tires? As load transfers while going around a corner, it’s the two tires on the outside of your car in the turn that are doing most of the work. The two on the inside are contributing (assuming they are in contact with the surface of the track, and not in the air!), but they’ll likely be at less than their limit, so it matters less what you’re doing with them.

The less load transfer you cause, the more equally-balanced the load is over all four tires, and therefore the more grip they have. One way to keep the car balanced is to cause as little load transfer as possible by turning the steering wheel slowly and smoothly. But if we turn it too slowly and smoothly, we’ll run off the track before making the corner! So, there’s a compromise: we want to turn the car as quickly as possible to change its direction, but as smoothly as possible at the same time. That’s just one compromise.

Another compromise is trading off cornering speed for exit speed. If you carry too much entry speed, you’ll be late getting back to power and slower down the next straightaway. But if your corner minimum speed is too slow, you’ll be accelerating from such a slow speed that you won’t be able to make up the difference. In fact, one way of getting to power early in a corner is to slow to one MPH entering it — you could stand on the gas pedal from the moment you turned into the corner! And you’d be slow heading down the next straightaway. So, finding the ideal balance between corner entry and minimum speed, and how early you can begin accelerating again is a compromise.

Getting these two compromises just right is part of driving at the limit. You could have your car on the absolute ragged edge of grip, and yet get these two compromises wrong. If so, you wouldn’t be as fast as you could possibly be. In other words, if you unbalanced the car, and got the min speed versus exit speed compromise wrong, you would be creating an artificially low limit.

Another way to think about the idea of creating an artificially low limit is this: If your car is capable of getting through a corner with a minimum speed of, let’s say, 60 MPH, but you slow it to 58 MPH, what happens? Likely, your internal traction sensors recognize that you have grip to work with, so you apply the throttle to make up for having over-slowed. In many cases, trying to “fix” the over-slowing with more throttle is going to cause the car to either understeer (from unloading the front tires), or oversteer (power oversteer from asking too much of the rear tires). And this is going to trick you into believing that you’re driving the limit, even though it’s 2 MPH slower than your car is capable of being driven — you’ve created the artificially low limit.

In terms of having the car at its limit through the corner, be clear on the fact that it must be doing something. By "something," I mean it must be understeering, oversteering, or some combination of the two (neutral steer). And not just in the last third of the corner (the exit phase). No, it must be doing something in the entry and mid-corner phases, too. And while we’re at it, in the brake zones, as well.

There is a limit, somewhere, though. The laws of physics eventually come into play when we’re driving. However, my experience says that few drivers are bumping up against those laws and the limits on a consistent basis. So, your mindset should be, “There’s always more.” But how do you know when you’re at the limit, or whether there’s more to be found in terms of lap time?

One way to know whether you’re driving your car at its limit is to have another driver — someone you know for sure is very fast — drive your car. If they go faster, then you know you have more work to do on your driving; if they don’t, then you have a pretty good idea that you’re getting the most out of your car. Of course, that still doesn’t mean that you’re getting everything out of your car, but you should be close. Again, there’s always more.